Last week, we talked about the grammatical dimensions of picking a perspective (also called point of view or POV) for your story.

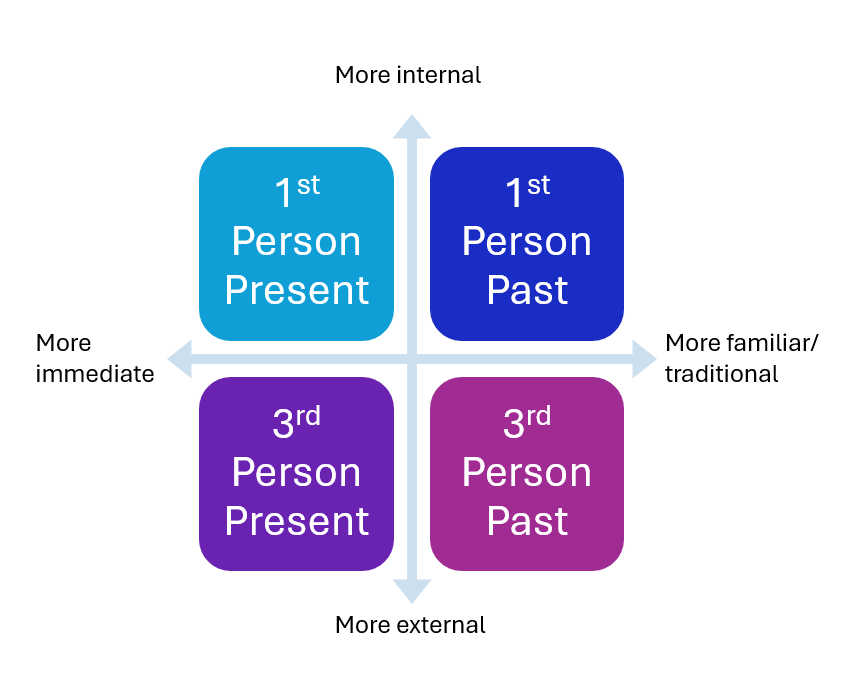

For a quick recap, you basically get two viable options for “person” and two for “tense”: that is, you can write in 1st or 3rd person (I or they), and you can write in past or present. This gives you a functional grid:

This is really the first consideration that an author has to make when writing, because it will determine the actual shape and grammar of every single sentence in the story. Not because the subject of every sentence has to be the narrator in a 1st person narrative, but because we have to consider the subject of every sentence relative to the narrator, whether that’s 1st, 2nd, or 3rd person.

The second consideration, though, is how broad that perspective will be. We have to add another axis to our chart: limited to omniscient. We may also include objective, perhaps as a true neutral, but that’s where our spectrum starts to fall apart (and I always forget that objective exists because in my mind it’s sort of a mode of omniscient–more on that later)

Generally these are only discussed in terms of 3rd person, but they are technically relevant in every grammatical position. These are not grammatical choices, but rather conceptual choices that will determine the scope of what you can and cannot say. They’re self-imposed limitations on your storytelling, but self-imposed limitations matter a lot.

Last time we talked about how comparisons to film and games, which are very common in discussing the craft of writing, don’t really hold up when discussing something that is fundamentally grammatical. The same thing holds true here to some degree because every medium and mode have their own strengths and weaknesses (or affordances and constraints if you want to be very technical), although here the metaphors are a little more useful. Consider, for instance, how it might break your immersion if a film director made most of the scenes in a film dark and moody with a lot of blue tones, but suddenly one scene is filled with as much color as a Kyary Pamyu Pamyu music video. That effect might be used on purpose, but that director had better have a darn good reason for the sudden splash! Or consider how confused a game player might be if a powerup suddenly looked different on the next level. As writers, we also strive for some internal consistency (except, of course, when we intentionally flout it) and our readers are trained by their own genre and reading knowledge to expect it from us.

So let’s dig back into our own reading training and review what limited, omniscient, and objective mean. In general these three terms will be used to describe 3rd person narrators, but they can technically be used for any combination.

The textbook definition is that limited perspective means that the reader only gets to see what one character sees. There’s a caveat here that it’s what one character sees at a time, because many very popular books of course have more than one perspective character, whether in 3rd or 1st person (for instance, Children of Blood and Bone). In general, first person narration sort of has to be limited, unless you are actually narrating from an omniscient character’s perspective (like 2nd person, rare and difficult to make work well, but technically possible). So for most people, thinking of limited perspective as “first person narration, but in 3rd person grammar” is going to work pretty well. It’s sort of like over-the-shoulder view in a video game. You generally see what the character sees, experience what the character experiences, but at some remove so you can watch them do it.

Omniscient perspectives are basically the opposite of limited perspectives. Omniscient literally means “all-knowing” (omni for all, scient as the same root word as science). Where, in a limited perspective, we only get to see and feel what a certain character sees and feels, omniscient allows us to see and feel what any character is seeing and feeling as relevant. This doesn’t mean you as the writer get to “head hop” without regard to narrative structure, but it does mean that you get to comment on the various ways that various characters might perceive the same thing. Omniscient narrators cover a huge range of tones and styles, ranging from having dialogue with characters’s innermost thoughts and even addressing the reader directly to being nearly invisible. In general, if you want an omniscient view, you need to use 3rd person, but that’s not an absolute rule (go ahead, write that experimental novel in 2nd person omniscient POV. Do it).

Objective perspectives are entirely uninterested in characters’ innermost thoughts and only report to the reader what a camera might capture. These are, likewise, almost universally 3rd person, although it could be done to have a Forrest Gump-like character who is not directly involved in the events you’re relating but somehow a perfect observer without commentary. In a sense, though, that’s the fiction we use with all 3rd person narrators anyway, isn’t it? That the narrator is somehow not part of any of the action but still able to relate it perfectly.

Let’s see if we can make an example. I’m going to narrate the exact same sequence of actions from each of these. Let’s tell a simple scene of a young adult celebrating a birthday alone. We’ll keep it 3rd person, past tense and just manipulate the limited/omniscient/objective variable.

Objective POV

Megan’s keys jingled as she shoved her apartment door open with her shoulder. She wore a white button-down blouse and a black pencil skirt. Her hair was brown and straight.

She closed the door behind her before she flipped on the light. The overhead light flickered. She tossed the keys on an Ikea stand by the door that had unopened mail stacked on top. The top letter was clearly marked as a final notice for a medical bill by the red stripe in the envelope window.

Megan opened the freezer. It only contained three things: two Marie Callender’s meals and a small boxed Carvel ice cream cake. She took the cake. She slid it out of its box and onto the counter and threw the box in an overflowing trash can. Then she took a spoon out of the sink full of dirty dishes, rinsed it off, and shoved it into the cake. “Happy birthday to me,” she said.

Notice how we get absolutely no commentary, but we still get lots of characterization. We can guess that Megan works in a customer-facing job, perhaps as a hotel clerk or a bank teller, based on her appearance. We can guess that her apartment isn’t very well maintained, so either she doesn’t care or (more likely) her landlord sucks. The medical bill tells us that she’s struggling with something financially and probably medically, too. There’s a lot here! But none of it is told directly by the narrator. The mode here feels almost photographic. This is how most films would introduce Megan. But let’s see what we can do with perspective to change the tone.

Limited POV

Megan struggled with her keys, but she struggled more with the door. It was always getting stuck. She shoved it with her shoulder. It figured that her birthday would suck, that she would have to work overtime and that the Karen in room 304 would be such a bitch.

She didn’t bother to change out of her work clothes. What was the point? She’d just be back in them in ten hours anyway. She closed the door and tossed her keys onto a stack of unopened bills from the hospital that was sitting on a cheap table. She turned on the light. It flickered. One more thing that didn’t work in this damn apartment. Fuck it. And fuck those bills. She wasn’t going to pay them.

The nearly-empty freezer was as depressing as the rest of the day, but she had been looking forward to that ice cream cake all day. It was small—all she could afford, really. That was fine. Perfect for just her to eat.

Megan glanced over the sink. There were dirty dishes there. Nearly every dish she owned. Oh well. She just rinsed off a spoon. That was all she needed.

“Happy birthday to me.”

We’ve got a very different tone here, because now we can hear more of Megan’s voice. She cusses a lot. She’s angry and tired and hungry. Our objective tone would have conveyed that eventually, of course, but this is just a clip.

The important part is we’re inside Megan’s head. We know not only that she has mounting medical bills, but we know how she feels about them and why she hasn’t opened them. We’re not inferring as much about her feelings.

But notice also we lost some of the visual aspect of the scene. This is more “telling” than the objective POV was “showing.” That’s not a bad thing. The question is: is it more important to convey the frustration that Megan feels about this moment in a close, intimate way, or is it more important to show how she feels alone by making the narration isolate her even from her own thoughts?

And we have a third option:

Omniscient POV

Megan struggled to open her door, the way that the five tenants before her had done. None of them had stayed long, and the landlord had done nothing but paint after each one left. Megan shoved the door open with her shoulder, an action so familiar now she didn’t even notice how it smarted. It definitely didn’t hurt as much as the guest in room 304’s insults today.

But even that was normal to Megan. She didn’t even bother changing out of her work clothes. Megan generally didn’t until it was time to hop in her unmade bed. She just tossed her keys on a cheap Ikea stand by the door and ignored the medical bills that were piled up there. She’d gotten so used to stacking them there unopened that she had not noticed the card from her aunt that arrived with them yesterday, which also lay unopened on the table.

Megan opened the freezer, which was nearly empty except for two Marie Callender’s microwave meals and a boxed Carvel ice cream cake. She pulled out the cake. She’d been looking forward to this all day. As she unboxed it on the counter, she realized that she didn’t have any clean dishes to eat it with. In her usual way, she just rinsed off the spoon she needed and stabbed it into the center of the cake.

“Happy birthday to me,” she said bitterly as her phone, left on silent, vainly tried to notify her that her aunt wanted to Facetime.

Oh, now we have a very different story! Now this is the story of a young person who feels alone, but who has at least one person who is trying to reach out to her, trying to remember her. The narrator tells the reader things that Megan doesn’t know and that a camera couldn’t show. That’s what makes this narrator omniscient.

Additional Considerations

One thing you probably noticed was that each iteration got longer. That’s not always going to be the case, but it is true that our omniscient narrator had a lot more details available to convey than our objective or limited narrators, at least in this story. And it is true that the objective narrator simply doesn’t get to make commentary, whereas the other two kinds of narrator do.

Personally, I love narrative commentary. For me, that’s a large part of the delight of a story, but that doesn’t mean I dislike objective narrators. Nor do I think any of these were easier to write.

The challenge of an objective narrator is in conveying the emotions and importance through describing actions and objects only. That requires a lot of control over the narration. You don’t get to say why the letters are unopened. You don’t get to say what Megan thinks about her landlord’s negligence, or even that the landlord is negligent. It’s the ultimate “show don’t tell” approach. And it’s hard.

The challenge of a limited narrator is balance. It’s tempting to do stream of consciousness in this style, and sometimes that’s what you want. But most of the time, it’s not. You have to balance external and internal description in limited narration. For me, switching between an internal and external space in a narration is a particular challenge—and a limited narrator is constantly juggling the two.

The challenge of an omniscient narrator is focus. Focus is built into the other two approaches, but an omniscient narrator has so much freedom that the author has to carefully weight what information out of literally all the available information is most important. Why does my omniscient narrator keep mentioning what Megan isn’t seeing? Obviously her aunt is going to play into the story, and less obviously I’m characterizing Megan as being basically blinded by her very reasonable frustration in this moment to the point that she’s ignoring the very thing she wants most, which is someone to show kindness to her and remember her. But too much head-hopping will confuse and frustrate your reader, who expects some sense of unity and purpose to everything you do as a writer. Many omniscient narrators, for this reason, wind up simply being multi-POV limited narrators (Terry Pratchett tended toward this mode).

So how are you going to pick which one to use?

Well, unlike the grammatical choice, this one doesn’t have to be made immediately upon writing your first sentence. The scope of your narrator’s knowledge, and consequently what you choose to show the reader when, can unfold as you work through your story and discover themes, motifs, character details, and other aspects of your story that will guide the choice. If you notice yourself tending toward objective, revise the rest to match; that’s probably the way you want to tell that story. If you notice yourself head-hopping, maybe you either want to limit to just one or two characters and need to rein in the hopping, or maybe that’s your narrative telling you it wants an omniscient narrator and you can lean into it, being deliberate about the hopping.

You’ll probably tend toward certain perspectives as a writer. That’s ok! While experimentation is vital to discovering your strengths and strengthening your weaknesses as a writer, you can also have a comfortable mode that you discover through experimentation. Perspective is likely to be part of that comfortable mode.

In the same way, some stories simply tell you what perspective they need. Next time we’ll talk about thematic elements and specific narrative structures such as epistolary and frame narratives, adding even more options and, hopefully, helpful heuristics to your POV choices.