My students are about a quarter through their coursework now. They’ve finished one of four projects. So I decided now would be a good time to assess how I’m doing in serving them as teacher.

I’ve seen a number of instructors suggesting weekly (or even more frequent) check-ins with students. I like that idea, but I think it works better if you are working at a level where students only have one or two teachers at a time (such as elementary school or graduate school). I imagine as a student I would have seen a weekly “How are you feeling?” poll as patronizing busywork, or, at best, just another thing I have to do, especially if all of my teachers were doing it. I’d get tired of the question. I don’t enjoy being asked “how are you?” more than maybe once a day; if I had to do four or five check-ins or wellness activities regularly for four or five courses, I’d resent it a lot.

But it’s important to check in occasionally, and on that I absolutely agree. So I decided to do it now, when I’m planning out the second half of the semester and when they’ve had a chance to experience the policies for a whole unit.

I don’t have all the data yet (only about 1/3 of students have completed the survey at the time I did this preliminary analysis), but I have enough to make some early conclusions.

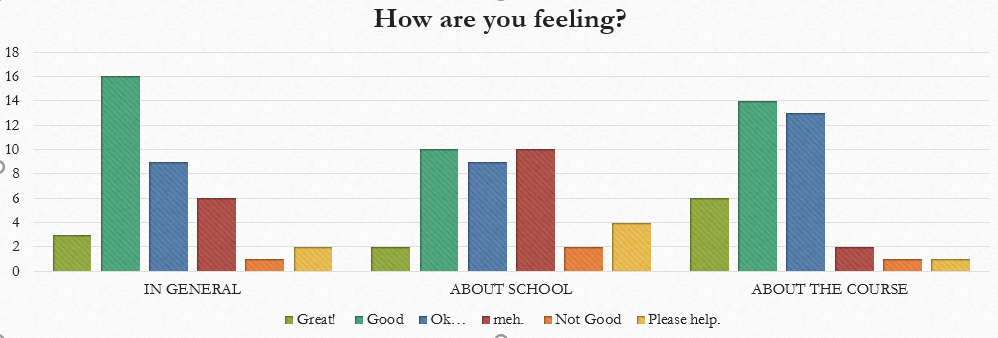

The good news is that my class apparently is not their main stress point in their academic My students report that, in general, they’re ok, not great, but that school in general is stressing them out. Considering that my institution has, of late, become the literal image of journalism covering universities (mis)handling the virus, I’m not surprised. That can’t feel good, to see a headline about virus outbreaks and see a photo of our own bell tower under it.

However, they report more positive feelings about my class specifically than about either school in general or their overall feelings at the moment. What this tells me is that my policies are doing their job of not adding extra stress to students. I know that my class isn’t exactly something anyone wants to take, but rather it’s merely required for the programs they want, so I try to design it humbly to not be too much of a stumbling block while still achieving curricular goals.

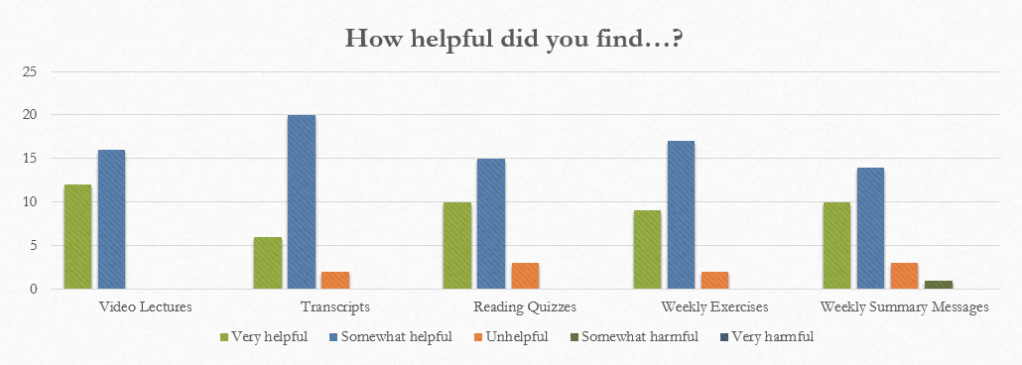

The other good news is that, in general, none of the interactions types I had them assess are being considered “harmful.” I had them rate the reading quizzes, the weekly exercises, and the weekly emails I send out on a scale from “very helpful” to “very harmful,” and in general all of the weekly tasks are ranking somewhere in “somewhat helpful”. That’s fine by me.

But what’s interesting to me is the contrast between how they ranked video lectures and what my YouTube views are saying. I use YouTube to host my video lectures because it’s easily embedded and has good captioning options. My YouTube views suggest about 1/3 of students are using the videos, at most. However, my survey data so far has no students at all marking the video lectures as unhelpful or harmful in any way. I can see a few different explanations for this.

One possibility is that the students who are using the video lectures are also the ones who complete their weekly tasks earlier in the week, so the survey responses so far are also the students viewing the lectures. I have about 1/3 of survey responses and I know about 1/3 of students are using the video option, so that’s possible.

It’s equally likely that the 1/3 of students who have responded are the ones who are active, engaged, and doing ok, so it may be premature to draw any real conclusions here, since so far it’s effectively self-selected data.

Another possibility is that it’s not consistently the same 1/3 of students viewing the video lectures and, in fact, I’m finding that most students use them at some point, even if they don’t use them all the time, resulting in a different 1/3 of students using them each week. This seems less likely to me, as students seem likely to get into a routine in a course, but it’s still quite possible. I have nearly 100 students total, so variation will happen.

A final possibility, which I take very seriously, is that they are saying what they think I want to hear, at least to some degree, either because they know that I’m going to see the data or because they aren’t really reflecting on their own learning processes enough yet to be critical.

That final possibility seems very likely because I used a Canvas quiz to generate the survey; that means that they’re interacting with it the same way that they’re interacting with their graded reading quizzes, which, despite being open-book and generous in retakes, are nevertheless assignments that reflect in their final grade in some way. I’m not sure that the students are aware that the responses, for this survey, are anonymous, because the interface doesn’t reinforce the anonymity, despite the anonymity being stressed in the instructions (no one reads instructions, and we have to design with that awareness).

In retrospect, I should have used a different platform for the survey. Canvas quizzes have an anonymous survey option, but it kind of sucks, and a different platform would have seemed safer to the students, since it wouldn’t be directly attached to Canvas where they do all their assessed work.

However, my take-away is that at least some of my policies seem to be having their intended effect. The students are stressed, but I think they’re going to be ok overall, and I’m reasonably assured that I’m not a major contributing factor to their stress.